Leslie Layton

ChicoSol / American Community Media

In the second verse of “Frontera,” the lead single on the newly-released album “Entremundos,” a fisherman makes the harrowing journey from his village in Sonora, Mexico, to the United States seeking work.

The fisherman’s story is the kind of story that the composers – members of the Chico band Debajito – know well. As part of the track “Frontera,” they hope it will break through the anti-immigrant ruckus and repression that has continued to darken life in this country.

“We have a relationship with that territory,” explained Debajito vocalist Dani Cornejo, whose mother’s family had emigrated from the Mexican state of Sonora. “Growing up, we went down there on a yearly basis. We would camp next to a fishermen’s village. That story is rooted in our relationship to the people of the La Manga fishing village.

“There’s a narrative around migration here — that people just come to suck the country dry of its resources,” said Dani, who with brother Pablo Kee Cornejo composed the music on “Entremundos.”

“What folks don’t understand is that there are push and pull factors for migration. There are factors pushing people out of their country of origin.”

Dani and his younger brother, Pablo, the Debajito frontman who teaches environmental engineering at Chico State, were raised in a community created by the push factors – the conditions that expel people from their countries. Their father fled Chile after the 1973 coup that marked the collapse of that country’s democracy, and their parents settled in Denver, Colo.

In Denver, the family was part of a community of exiliados and music was a huge part of their lives. Dani and Pablo grew up among Latino immigrants, many of whom, like their father, had sought exile because of political repression imposed by U.S.-backed military dictatorships and authoritarian regimes.

“Entremundos,” released earlier this month, is Debajito’s first album and was produced outside any corporate framework with the help of Chico State Recording Arts students. The album explores themes of migration, belonging and unity in keeping with what the band says is its mission — to produce music that serves as a platform for resistance.

That resistance can take many forms depending on how the music is heard. “A lot of people will come to a Debajto show just to dance and have fun,” Pablo said.

“And that joy is in itself a form of resistance,” the brothers said, almost — but not quite — in unison.

In the communities comprised of Latin Americans who fled their home countries in the 70s and 80s, resistance music became enmeshed in the culture. The Cornejo brothers were shaped by the influence of Latin America’s remarkable New Song (Nueva Canción Latinoamericana) movement that blended protest and folk.

That movement produced talented artists like Chile’s Victor Jara, who was tortured and killed by the brutal Pinochet regime, which came to power in the coup with the support of the United States.

Members of the band that was at one time under Jara’s direction — Quilapayún – sometimes stayed with the Cornejo family in Denver. (Quilapayún was forced into exile, but only after it had made the song “El Pueblo Unido Jamás Será Vencido” (“The People United Will Never Be Defeated”) a classic protest song throughout the continent.

“The first music that I remember hearing as a child was Nueva Canción Latinoamericana,” Dani said in a recent interview in the sunny backyard of Pablo’s Chico home. “But musically speaking, it wasn’t just listening to the records. Our father could play that music, and he had the instruments, and he made those instruments accessible to us.”

Pablo said he and his siblings were shaped by a particular “iteration” of the Nueva Canción movement. “It was passed to us as borderless music in the sense of honoring the roots of music throughout Latin America,” Pablo said.

Dani said it was a logical step for the brothers to move into hip-hop, “which is also rooted in resistance, in struggle, in movement,” and punk rock. And those genres gave them a “template for composition.”

In the track “!Qué Pasa!” on “Entremundos,” verses make references to Chico and the challenges facing California immigrants in general. Pablo’s version includes the lines:

“Que lo que pasa

This is for the raza

This is for the anti fascistas en la casa

See you at the marcha.”

In another line of verse, he acknowledges a woman he had seen at Chico’s City Plaza who appeared to be homeless.

This reporter first heard them play at Tender Loving Coffee in 2020; then as now, the music was danceably upbeat with suggestions of hip-hop, cumbia, Latin alternative and even, thematically, Nueva Canción. They were producing a fusion that was unusual if not entirely new to Chico.

Sometime before that show, Pablo had met a Chico resident, Luis Castillo, at that same café. Castillo is a Peruvian who had settled in Chico with his American wife, Kristen, and plays the cajon – a wooden box the musician sits on as he plays percussion. Castillo joined Debajito and plays a variety of percussion instruments.

He hails from the town of Chincha, where the cajon has its roots in the heart of Afro-Peruvian culture. In that part of South America as well, people were struggling under repressive regimes, but also finding community and joy in music. Castillo said he loves the message that permeates Debajito’s music.

“Everyone puts in their own musical style,” Castillo said, “and in the end we send a message: Unity.”

Wayne “Weezy” Moore joined Debajito when it was in its early formative stage after moving to Chico from Detroit, Mich., to add intricate rhythms with the hi-hat and bass drum. Moore isn’t bilingual but say he’s “on board” with the message.

“When Pablo’s rapping I have to ask for translations, but the message that comes across is a message I agree with: Peace, unity, love,” Moore said.

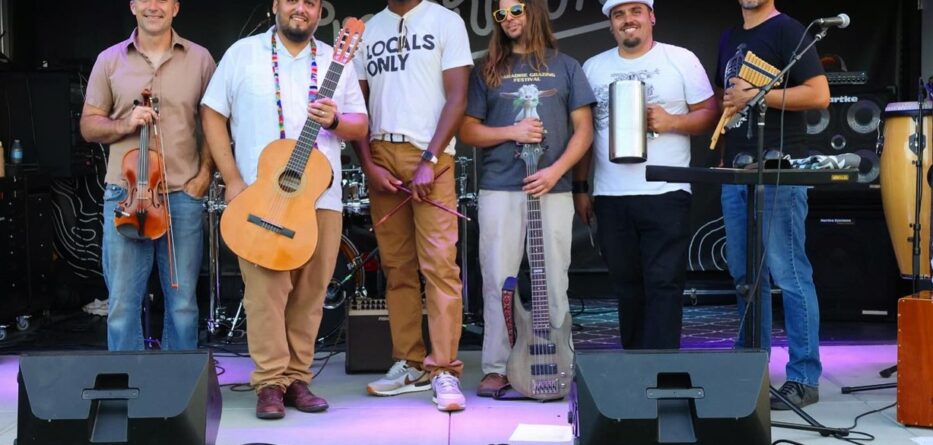

The band that advertises itself as “borderless” also includes bassist Austin Petersen, violinist Peter Washington and another percussionist, Juan Carlos Bermejo. Andean instruments like the zampoña y quena are often incorporated — instruments that were banned or suppressed during the tenure of Augusto Pinochet that lasted until 1990.

“Each one of these instruments has its own story of resistance,” said Dani, who teaches ethnic studies at a Bay Area college. The concepts behind some African percussion rhythms came to the Americas with enslaved people.

The track “Frontera” was written by Dani, Pablo, and another brother, Elias, during the 2006 protests against anti-immigrant legislation. Pablo said they wrote new verses this year “to make it related to what’s going on right now.”

“A lot of corporate-backed music will have a message that is not affirming to humanity,” Pablo said. “The music can be incredibly catchy. We intend to use that model and flip it around. The ability to gather community together, to dance, to release, to feel joy — I do think that is a form of resistance, especially in these times when it’s easy to feel defeated.”

Leslie Layton is editor of ChicoSol where this story was originally published. It was produced in collaboration with Aquí Estamos/Here We Stand, an American Community Media immigration reporting project.