When Monica walked through the door of her home after three months in the Adelanto ICE Processing Center, in Adelanto, California, her six-year-old daughter’s first words cut deep: ‘Why did you abandon us?’.

For Monica (we are not using her real name to protect her privacy), detention was harrowing, but explaining to her child that she hadn’t left by choice—that immigration officers had taken her—was even harder.

On an early June morning in California’s Central Valley, Monica was riding in her partner’s car with her two siblings on the way to work at a local farm when immigration agents signaled for them to stop at a traffic light. As the car came to a halt, everyone inside fled—except Monica, who was paralyzed by fear and unable to leave the vehicle.

The agents told Monica they were looking for her partner, but since he had escaped, they would take her instead. “They put shackles on my hands, on my ankles, and a chain around my waist,” recalled Monica, speaking in Spanish.

After being taken to different immigration offices, first in Camarillo, along California’s Central Coast, and then Santa Ana, farther south in Orange County, she was finally transferred to the Adelanto Detention Center, about two hours east of Los Angeles and more than 200 miles from her home.

A 2015 study by the American Immigration Council found that 64% of detainees were held at least once in a facility outside a major urban area, and 22% were confined more than 120 miles from the nearest nonprofit immigration attorney. The study also found that confinement in privately operated facilities or in locations outside major cities was linked to significantly longer periods of detention.

Immigrant rights advocates say that the practice of shipping migrants off to remote locations has increased under the Trump Administration, with detainees being held in states far removed from their homes.

That was the case for university students Mahmoud Khalil and Rümeysa Öztürk, both of whom were held at a center in rural Louisiana despite first being arrested in New York and Massachusetts, respectively.

Homero López is legal director with Immigration Services and Legal Advocacy (ISLA) in New Orleans. Speaking at an immigration policy conference in Washington, DC, he said the administration has “weaponized” the practice of sending migrants to locations far removed from family and legal representation.

During her arrest, Monica pleaded with agents to let her go, asking them to consider that she had three children waiting for her at home. Her request was ignored. She would spend the next three months in the Adelanto ICE Processing Center, where she had no contact with either her husband or children, who were afraid of being detained themselves.

“It’s always cold there, like an icebox,” she said, recalling how she and other detainees often got sick from the freezing temperatures in the room.

Monica also struggled with the low quality of the food. She remembers one meal when she was served under cooked chicken. “I ate it because I was very hungry, but it was very raw,” she said, adding that it gave her diarrhea for a week. She explained that other detainees faced similar problems.

In September, the Los Angeles Times reported the death of Ismael Ayala-Uribe (39)while in custody at the Adelanto ICE Processing Center. Two weeks after his arrival, Ayala-Uribe complained of a cough, fever, and severe pain. Internal emails obtained by the Times show that staff considered his condition potentially life-threatening. He was rushed in a wheelchair to the detention medical center but returned to his dorm just 90 minutes later. Four days afterward, he was pronounced dead.

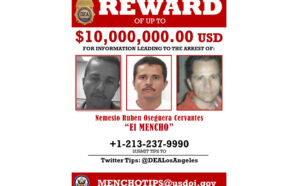

The Adelanto center is owned by The GEO Group, a private prison company that contracts with the federal government. The company currently operates four immigrant detention facilities in California and has been accused of multiple violations, including a 2021 class action suit for chemical exposure.

While California empowered counties to inspect conditions at the centers, three of the four counties given oversight powers have not done so, or at least not beyond basic reviews of food, according to CalMatters.

During her time in Adelanto, a fellow detainee connected Monica with a lawyer who took her case and secured her release on a $5,000 bond—a debt her family is now struggling to pay.

The conditions of her detention also took a toll on her emotional health and that of her family. She remembers crying every day, thinking of her husband and children.

“When I returned home, my children didn’t want to come near me,” she recalled. “I have a two-year-old boy, and he didn’t want to come near me.” She added, “Only now is he starting to come closer.”

Claudia Caceres of Tu Tiempo Digital provided reporting for this story.