Two decades ago, California legislators added a new weapon to the state’s growing arsenal of gun-control measures, already among the toughest in the nation. Their motivation came from 2,000 miles away in a shaken Chicago suburb.

It was there that a gunman opened fire in an engine factory where he’d worked for nearly 40 years. He killed four people and wounded four others before pulling the trigger on himself. It was soon revealed that some of the weapons he smuggled inside should have been earlier confiscated because of his past criminal convictions.

In the wake of the rampage, and with lofty expectations, California became the first state in the country to create a database identifying thousands of people who’d legally purchased guns but were now deemed too dangerous to be armed.

In a rare display of bipartisanship — especially on an issue as fractious as gun control — the California Legislature wanted to give state and local authorities a methodical way to remove firearms from individuals who’d lost their right to bear them because of violent crimes, serious mental health issues or active restraining orders.

But what seemed at the time like a straight-forward approach to the enforcement of existing gun laws has instead become mired in chronic shortcomings, failing for years to make good on its potential. Successive administrations have vowed to fix the problems, but all have fallen short.

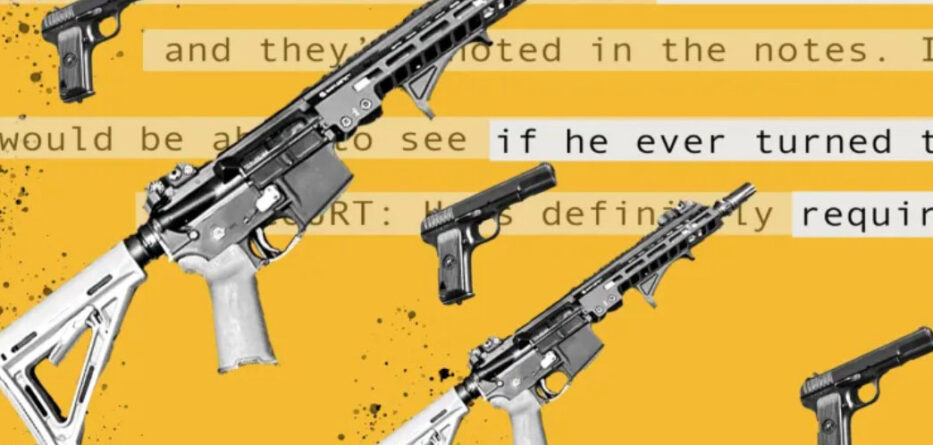

Today, the state is struggling to recover thousands of guns from people who have been ordered to surrender them. At the start of the year, the list compiled by the state Department of Justice had swelled to 24,000 individuals, the most ever. The pandemic only worsened the mounting backlog of cases when some state Justice Department agents were pulled from field enforcement.

“We are lucky to have a system that tells us this information,” said Julia Weber, a former supervising attorney for the state courts’ administration who now works on gun policy issues for the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. “But it’s disheartening. It’s a failure of the promise of the system.”

CalMatters spent three months examining the layered troubles of the Armed and Prohibited Persons System, interviewing current and former law enforcement officers, gun control advocates, lawmakers and researchers. The news outlet also contacted hundreds of law enforcement agencies across California to assess their engagement — or lack thereof — with the system.

The state would not provide names of individuals in its database, citing confidentiality restrictions. But CalMatters obtained a small sampling dating back to March through separate requests to local law enforcement agencies that had received state Justice Department information for their jurisdictions. They provide a glimpse of the stakes behind the statistics.

In Santa Paula, a woman in the database has been ordered to surrender her guns because of a mental health-related prohibition. She’s listed as having 22 of them. In Ukiah, an accused domestic abuser is believed to have 44 guns. A Central Valley man awaiting trial on a rape charge for three years has remained armed despite a court order requiring him to hand over his firearm.

One of the names in the database stunned Corina Arias. In 2016, the Kings County grandmother was punched by her next-door neighbor, John Marshall Smith, who was convicted of misdemeanor battery. The conviction carried a 10-year ban on owning a gun in California.

“I can’t even believe they’d allow him to be armed,” Arias said when told her attacker was listed by the state in March as having failed to surrender his gun. “It’s a complete shock.” (CalMatters was unable to locate Smith, and his attorney in the case is deceased.)

Top-to-bottom problems stymie success

The system’s effectiveness, CalMatters found, is being undermined on numerous fronts.

On the ground, the envisioned collaboration between state and local criminal justice officials to confiscate firearms has been scattershot, at best. Some police departments say they had no idea they even had access to monthly state reports identifying individuals in their jurisdictions who remain unlawfully armed.

At the same time, many judges have done little to ensure their orders requiring gun relinquishments are executed, worsening the backlog and potentially putting the public’s safety at risk.

Meanwhile, understaffed state agents in the Bureau of Firearms are often outmatched by the onslaught of new cases every day from throughout California. Each one must be checked and cross-checked by hand across multiple criminal justice databases before being added to the prohibited-persons list. Simply put, the additions are coming faster than the subtractions.

The work-intensive process and outmoded technology has led some in law enforcement to question the database’s reliability. They say they’ve discovered errors during field operations and that investigations based on the list are a waste of resources.

Experts on the system — who note that thousands of guns have, in fact, been removed from individuals — say stakeholders throughout government must summon the resolve to finally fix the system’s deepening problems.

“We’ve made a decision as a society that there are people who, for a constellation of reasons, should not be allowed to have firearms. Are we going to enforce that social decision or not?” asked Garen Wintemute, director of the Violence Prevention Research Program at UC Davis.

To be sure, a person’s inclusion on the list does not mean he or she will act violently with a legally purchased but unlawfully possessed weapon. Gun control advocates struggled to identify shootings that might have been prevented had authorities successfully retrieved firearms. Officials acknowledge that some people on the list may have already surrendered their weapons.

Although the state does not track how many individuals, if any, commit crimes while they continue to remain armed, the agency has good reason to be concerned.

“We’ve made a decision as a society that there are people who should not be allowed to have firearms. Are we going to enforce that social decision or not?”

GAREN WINTEMUTE, DIRECTOR OF THE VIOLENCE PREVENTION RESEARCH PROGRAM AT UC DAVIS

Last year, agents recovered 12 handguns, four rifles, two shotguns, one assault weapon and thousands of rounds of ammunition from a person listed in the database as having 24 firearms. One of the handguns was loaded and unsecured in a bedroom closet of the Norwalk home, where a 16-year-old and 2-year-old also lived.

The previous year, law enforcement authorities discovered that a Los Angeles County man in the database was trafficking illegal weapons. They found a tactical vest and a pipe bomb in his home.

In 2020, as the pandemic spread across the months, nearly 300 people on the list tried to buy ammunition but were denied the purchases during background checks mandated in California, according to the Justice Department. Agents investigated and closed 73 cases involving those people, recovering 96 guns.

At the time of its adoption, the Armed and Prohibited Persons System was seen as the low-hanging fruit of gun-control measures—taking firearms from known owners who legally shouldn’t have them.

But today, the inability of state and local agencies to make it work as envisioned has raised questions about how they can begin to confront the wider menace posed by the thousands of illegal firearms circulating throughout California or the new wave of untraceable “ghost guns,” assembled at home from mail-order kits.

“It’s very frustrating to see that we have such a hard time implementing firearms removals in situations where we have all the information in front of us,” said Weber of the Giffords Law Center. “It doesn’t give the public a lot of confidence in our ability to tackle a lot of these more complex firearm issues.”

Stephen Lindley spent more than 15 years in the state Justice Department, including nearly a decade in charge of the Bureau of Firearms before leaving in 2018. He said he was proud of California’s database and its successes removing weapons from potentially dangerous and suicidal individuals.

But he said he also saw up close the many obstacles. You can’t keep adding people to the list, he said, without making sure weapons are being removed from people, too.

“We’re no longer at the front of the pack here,” he said.

A vow to fix California’s gun law — again

During his confirmation hearings in summer 2021, State Attorney General Rob Bonta was peppered with questions from lawmakers on how he planned to fix the system. The discussion mostly focused on the need to modernize the database and hire additional agents to investigate cases.

At the start of this year, there were 75 authorized positions in the Bureau of Firearms unit responsible for the Armed and Prohibited Persons System, nicknamed APPS, including special agents, supervisors and trainees. But a third of those spots were vacant, meaning that some 50 individuals in six offices across California were primarily responsible for tens of thousands of guns.

In the past, money has not been the answer.

Following the Newtown, Conn., elementary school mass shooting in 2012, for example, the state added $24 million to address what was then a rising backlog of armed individuals. With that funding, the Justice Department said it could reduce the backlog by 40% over three years, bringing total cases down to 11,900.

It didn’t work, largely because the agency had trouble recruiting and keeping staff.

Bonta said in an interview that he wants to address those staffing shortages and keep pace with advances in technology so overburdened agents don’t have to grapple with a hodge-podge of nearly a dozen outdated databases to create a reliable list. As it stands now, the department can’t even determine the precise breadth of the backlog, including how many cases have remained unresolved for more than six months.

“It is a nation leading system, something that California should be proud of,” Bonta said. “We’re committed to making progress in reducing the APPS list and hope to be able to show you the outcomes and data in the months and year ahead that demonstrates that.”

Holes on the front lines

Lost in all the talk about funding and modernization has been an arguably bigger obstacle to success — how to get hundreds of local law enforcement agencies to pick up a heavier share of the burden, as legislators initially envisioned. Building the list is one thing, getting the guns is another.

The Justice Department has for years prepared a monthly report for local agencies across the state showing who in their jurisdictions is in the database. But either the word hasn’t gotten through or the will to act among some local police hasn’t been strong.

Lindley, the former head of the state firearms bureau, said that under his watch the state sent the monthly reports as both a document and spreadsheet so departments could filter data to, say, focus on just local residents with a history of domestic violence or severe mental health issues.

But “agencies didn’t do shit with them,” Lindley said. He later softened his criticism, saying some, like the Los Angeles Police Department, did set up local programs to confiscate the guns. But many agencies didn’t engage.

“The APPS program saves lives,” Lindley said. “And if more agencies invested just a little bit of time into doing that in their own jurisdictions, it would be very beneficial.”

CalMatters asked 400 local law enforcement agencies across California for the most recent monthly reports they’d received regarding unlawfully armed people in their jurisdictions.

About 80 departments indicated they were aware of the report but declined to provide a copy, citing various public records exemptions. Many departments simply didn’t respond.

But more than 150 agencies wrote back saying they didn’t have any such reports. Although it’s possible an officer in one of those agencies may have obtained information directly through the Justice Department’s website, numerous police officials said they had no idea what CalMatters was asking about.

“I have been the police chief here for almost eight years. We have never received a report from anyone regarding who has guns that they should not have,” Orange Cove’s police chief wrote in an email. “I have never heard of such a report.”

The same went for Leslie Easley, a records administrator at the Lassen County Sheriff’s Office. “As far as I know, there is no report like that. I’ve never seen one in 15 years here.”

While on the phone with a CalMatters reporter, she logged into a portal where the state shares information with local law enforcement agencies. She tried searching for a monthly armed and prohibited persons report but got only an automated message saying her search yielded no results.

And it wasn’t just smaller agencies that said they were unaware of the reports.

Bottom of Form

“I’ve never heard of this,” said Maryann Weiman, a senior administrative analyst with the Stockton Police Department. “That might have been nice to know about.” Weiman said she couldn’t rule out the possibility that someone in her 400-person department receives an email. But if the department was using such a document, Weiman said, she’d know about it.

One Northern California department indicated that it would start getting reports as a result of CalMatters’ records request.

“After checking our files, we found that our agency was not receiving the Armed Prohibited Persons System reports on a monthly or any basis. As such, we have no reports that are subject to release,” Willits Police Chief Fabian E. Lizarraga wrote in an email. “We have now instituted steps to start receiving these reports through the Department of Justice. Thank you.”

“I have been the police chief here for almost eight years. We have never received a report from anyone regarding who has guns that they should not have.”

MARTY RIVERA, ORANGE COVE’S POLICE CHIEF

Questions surrounding the reports publicly surfaced as a result of a 2008 shooting in the Southern California city of Baldwin Park.

In that case, Roy Perez shot and killed his mother, a neighbor and the neighbor’s 4-year-old daughter with a handgun he bought legally in 2004. In the aftermath, authorities acknowledged that Perez was in the state’s database and should have had his guns confiscated three years earlier because of mental health issues.

In a 2011 article on California’s database system, The New York Times noted that Baldwin Park police had failed to regularly read the state’s locally-tailored reports. “Nobody knew where the e-mail was or where it was going,” one lieutenant was quoted as saying.

A decade later, the list apparently still remains a mystery to the Baldwin Park Police Department.

Through a public records request, CalMatters asked the department for the latest monthly armed prohibited person report.

“There are no responsive documents because the City does not have the report you are requesting,” wrote an attorney representing Baldwin Park. Police department officials did not respond to multiple requests to clarify whether they were aware of the reports.

Every weapon a challenge

The system’s mounting backlog reflects, in part, the time-consuming hurdles authorities confront in trying to get thousands of recalcitrant individuals to surrender their firearms — or to verify they’ve already done so. Each one presents its own formidable complexities in a system that, despite the state’s centralized database, is often hit-and-miss locally.

Take the case of Roger Martin, who was on the list supplied to Kings County law enforcement in March and obtained by CalMatters. Last year, court records show, he was accused of domestic violence in both criminal and family courts.

Martin, 60, allegedly shoved his wife so hard she fell face first onto the floor and broke her wrist, according to a restraining order request filed by her attorney in September 2020. In the request, the court was informed that Martin possessed firearms.

Martin was arrested and charged criminally for the alleged attack, ultimately pleading no contest to a misdemeanor domestic violence charge.

He was required to surrender his guns in early September when he was first served with the family court’s temporary restraining order. Two months later, the judge presiding over the criminal case issued a protective order, which also barred him from having guns.

Despite the two court orders, Martin for months failed to surrender numerous firearms.

Court records show that in April of this year, the family court appointed a local lawyer to retrieve the guns and give them to Martin’s attorney, who would ensure his client no longer had access to them. Records submitted in the case show that Martin transferred 12 firearms on April 12 for no money to a gun shop in Arizona — seven months after he was ordered to relinquish them.

Attorney David Lange, who represents Martin’s wife, is challenging the transfers because he believes the guns should have been transferred to a licensed dealer in California, as he argues the law requires. What’s more, he said the gun dealer in Arizona is Martin’s friend.

“He still has access to these guns. I believe this is a sham transfer,” said Lange, who has asked the family court to hold Martin in contempt.

Barring someone from having a gun for a few years, Lange said, allows for a “cooling off period” and gives “time for someone to heal and get over their anger. But it only works if we can actually get the guns away from them. Nobody is following through to make sure it actually happens.”

Martin’s attorney in the criminal case referred questions to his family court lawyer, who handled the weapons transfer. That attorney declined to comment.

In the field, police see flaws up-close

Law enforcement officers, meanwhile, face their own roadblocks.

The database is what some refer to as a “pointer system.” It points officers toward possible guns, but it takes investigation and planning to determine if a firearm should be seized and how to do it.

Merely being in the database does not rise to the level of probable cause for authorities to obtain a search warrant and gain access to a home. Instead, officers must resort to knocking on doors, getting people to voluntarily acknowledge they still possess firearms and then convincing them to hand them over — no small feat.

Troy Newton spent 22 years in the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Department before retiring in 2019. Several years ago, he was part of a small team his department assembled to recover guns from people on the list. But it was a bust, he said.

Newton said the team knocked on doors for all of one night before abandoning the effort as a waste of resources that could be directed toward more pressing violent crime problems. Some individuals the team contacted, he said, easily provided proof their guns had been sold long ago, while others claimed they had gotten rid of them but could provide no evidence.

“There was just no way to verify,” Newton said, adding that the state “has no idea who has guns and who’s turned them in.”

Department of Justice officials acknowledge their database isn’t fail-safe.

In 2018, for example, they found that local police routinely failed to update the state’s databases after taking a gun. As a result, state agents concluded that in more than 8% of their investigations that year, the guns in question were already in law enforcement custody.

Even when the information is correct, some people might be on the list because of an apparent misunderstanding or paperwork issue, not because they’re trying to illegally keep their guns.

Christopher Blankenship, a former reserve officer for the Santa Paula Police Department, said he had to “jump through hoops” to get his name off the list. In 2013, he pleaded guilty to a felony for a drunken, off-duty crash that killed another officer. The conviction resulted in a lifetime ban on firearms ownership.

CalMatters contacted Blankenship to determine why, eight years after his conviction, he was among eight individuals who remained listed as unlawfully armed as of March, according to information released by Santa Paula police through a public records request.

Blankenship said the Justice Department informed him about five or six years ago that he was in the Armed and Prohibited Persons System as owning two guns. He said he told the agency that he’d given both away as gifts — one to his brother, one to a friend — and provided photos to back up his account. He said he also signed a form attesting that he no longer owned them.

“As far as I knew that was done, taken care,” he said.

But in March, he said, two Ventura County Sheriff’s deputies knocked on his door. Their department is one of four participating in a pilot project in which local agencies help recover firearms from individuals on the list, an effort that got a $10 million funding boost from the Legislature this year.

Blankenship said they told him he’d have to legally transfer ownership of the gifted weapons in California, otherwise he’d remain in the database.

So in late March, Blackenship said, he drove north to a gun store in Redding, where he met his Oregon friend and transferred ownership of the firearm. He did the same with his brother at a store in Oxnard.

Despite the hassle, Blankenship said, he appreciates the importance of the state’s database. Whether it’s getting guns from dangerous individuals or simply ensuring they’re properly accounted for, “it’s just a good way of making sure they’re handled in a legal, proper way.”

Courting danger

One logical place to start confronting the backlog of unlawfully possessed weapons, advocates say, is in the courts, where judges issue the directives prohibiting individuals from possessing firearms because of convictions and restraining orders.

But CalMatters found that California judges, for a variety of reasons, are failing to ensure that their orders are being followed. This forces the Justice Department and local police to play catch-up months later after the names end up in the state’s database.

Department officials flagged the problem in their last two annual reports on the system.

They noted that the percentage of individuals with felony convictions in the database climbed from 47% to 54% between 2019 and 2020, suggesting that “relinquishment regulations at the time of conviction are not being effectively implemented.”

Over the years, there have been efforts — including legislation and voter-approved measures — to ensure guns are being surrendered earlier, at the courthouse level, but many have been stymied by budget barriers, hiring hurdles, technological issues or inconsistent enforcement.

The state has failed, for example, to fully fund a mandate requiring California’s county courts to confiscate or enforce the transfer of firearms “at the time of conviction when an individual is prohibited due to a felony or qualifying misdemeanor,” the Justice Department noted in its 2020 annual report.

A 2001 law also has failed to live up to its billing.

It requires family courts to perform background checks on individuals before issuing domestic violence restraining orders to determine, among other things, criminal histories. A later law expanded the checks to include a review of the state’s vast database of all legal weapons sales. If there’s a match, judges are empowered to convene hearings and hold gun owners in contempt to ensure their weapons are surrendered.

In practice, this hasn’t always happened.

The full background checks only applied to courts with the resources to afford them. The state Judicial Council was legislatively tasked with determining which courts were too hard-pressed to comply. But that analysis was never done. To this day, state court administrators do not know who’s doing rigorous background checks and who’s not.

In addition, many judges lack access to a confidential Justice Department database that includes all weapons sales, to match against individuals in their courtrooms accused of acts that would bar gun ownership.

Records show that 20% of people in the Armed and Prohibited Persons System — nearly 4,600 gun owners — are under restraining orders.

“Why don’t we give judges access to the purchase records?” said gun researcher Wintemute, who is studying the state’s system. “What if they could say, ‘I got it right here in the computer…You’ve got guns and we’re going to send you home with the bailiff and we want those guns now.’ Just get it done.”

Only 28 superior courts — fewer than half — have access to the Justice Department’s web portal, which includes firearm ownership records and other law enforcement databases, according to the Attorney General’s Office. Although some courts told CalMatters that local sheriff’s offices check firearm ownership for them in domestic violence cases, others acknowledged they’re unable to regularly get such information.

Confusion was evident in the response of Placer County to CalMatters’ queries. The court there initially said it had access to criminal histories, but not firearms ownership. After follow-up questions, a spokesman said the court discovered it did have access to that information and would now use it in domestic violence cases.

Even when family court judges learn an alleged abuser is armed, they don’t always require proof that guns are surrendered.

Too often it’s an “honor system,” said Allison Kephart, the legal director of Weave, a nonprofit that helps domestic abuse survivors in Sacramento County. “It falls on the victim to come back to the court and say, ‘Excuse me, your honor, you told this person they needed to turn their gun in. And I don’t believe they have.’”

A bill advancing through the Legislature, Senate Bill 320, would force family court judges to do more to ensure abusers surrender their weapons. Although a similar bill failed last session, this one has little opposition.

Defiantly armed and dangerous

The price of legislative inertia or judicial inaction can be harrowingly high.

In June 2019, a Fremont woman asked the family court in Alameda County to issue a domestic violence restraining order against her husband, Treveonn White. She alleged that he strangled her and threatened to shoot her.

CalMatters learned of the case through a public records request to county prosecutors for information on individuals with restraining orders who were later charged with firearms possession. CalMatters does not identify alleged abuse victims without their consent.

During a hearing, the 22-year-old woman warned a superior court commissioner, who functions like a judge, that White owned two handguns. Records confirm that he had two registered firearms.

“He’s definitely required to surrender those,” the court commissioner replied, according to hearing transcripts.

The woman was granted a restraining order, which directed White to hand over any guns in his possession to a law enforcement agency or licensed dealer. “The judge will ask you for proof that you did so,” the order states.

There’s no record that the court followed through with the warning—not in hearing transcripts or any documents available in the court file.

There is, however, evidence that White’s wife continued to fear for her safety. Twice, she filed documents with the court saying her husband remained armed. She wanted the court to force him to surrender the weapons but she missed one hearing on her request and was told she incorrectly filled out the paperwork a second time.

Just weeks later, in the middle of the night, White began leaving menacing messages on his wife’s phone.

“I can’t wait. I can’t. I’ll be right there and I’ll be watching when I blow your f—ing brains out,” he said, according to allegations later filed in criminal court.

Terrified, the woman called the police. Fremont officers raced to her house, where they found White parked in the darkness in a black Kia. He had a .22-caliber handgun and a magazine loaded with nine rounds.

White was charged with making criminal threats and possessing a firearm, despite being the subject of a restraining order. Last month he pleaded no contest to illegally carrying a concealed weapon, and the District Attorney’s Office dropped the other charges.

The Alameda County Public Defender’s Office declined to comment on the case. So, too, did a court spokesman. Nor would the Justice Department confirm whether White was in the state’s Armed and Prohibited Persons System.

But according to a declaration police filed in the case, White did know about the restraining order. When officers asked him why he hadn’t surrendered his firearms, White responded: “F—k that.”