TEGUCIGALPA – A teenage boy is crouched to the side of a building entrance, his tear-stained face staring blankly past the police ribbon stretched across the intersection. Inside, a group of indigenous Hondurans are gathered, having traveled to the capital to denounce what they say is the government’s ongoing theft of their ancestral lands.

“Sorry about all of this,” the security guard remarks, gesturing to the scene around him. “This is Honduras.”

On November 28, Hondurans will cast their vote for the Central American nation’s next president. The election comes amid a pall of violence and socioeconomic conditions that rank alongside Haiti as among the lowest in the western hemisphere. For many, Honduras warrants the status of a failed state, and yet there are those here who say the coming elections offer the best — and perhaps last — chance to turn things around.

“These elections are an opportunity to recover the democratic process and to confront the multiple crises impacting the country,” says Gustavo Irias, executive director of CESPAD, a nonprofit that advocates on behalf of Honduras’ marginalized communities. “This is a chance for Honduras to recover its sense as a nation.”

That sense of nationhood was shattered in 2009 when the Honduran military ousted former president Manuel Zelaya in a move the United States is thought to have played more than a passive role in. Since then, Honduras has remained under the control of the right-leaning National Party, currently led by President Juan Orlando Hernández, now finishing his second term under a cloud of suspicion over potential links to narco traffickers.

The candidates seeking to replace him include National Party favorite and current Tegucigalpa Mayor Nasry Asfura, or “Papi” as he is known, and the Libre Party’s Xiomara Castro, wife to ousted former president Zelaya, who has promised to curb the excesses of the free-market policies embraced by her opponent while forging closer ties to China.

Violence, corruption, and poverty, meanwhile, remain endemic features to life here. According to the World Bank, as of 2019, 15% of Hondurans live on less than $2 per day, conditions likely worsened by Covid 19 and the impact of hurricanes Eta and Iota last year, with projections of more than half the country falling below the poverty line in 2020.

Such conditions are fueling an exodus of migrants from the country, with data from this year showing 168,546 separate reports of Hondurans detained by immigration officials in the United States and Mexico, according to a June report from the Migration Policy Institute. The report noted 1-in-5 Hondurans express a desire to leave the country, with reasons ranging from food insecurity to fear of assault and unemployment.

For some in the capital the coming elections offer little hope for improvement.

“Nothing is going to change,” says Victor Manuel Mayorga, a public employee who says he has not been able to retire because the government has stolen the state’s pension funds. At 79, Mayorga is part of a tiny minority of senior citizens in a country where the median age is just 24 years old.

Sitting in the city’s central plaza talking soccer with friends, he bemoans the lack of education and health care, and accuses officials of all political stripes of abandoning the country. “I believe in democracy, but in Honduras it is broken. It’s been broken since the coup.”

Still, not everyone is as despairing.

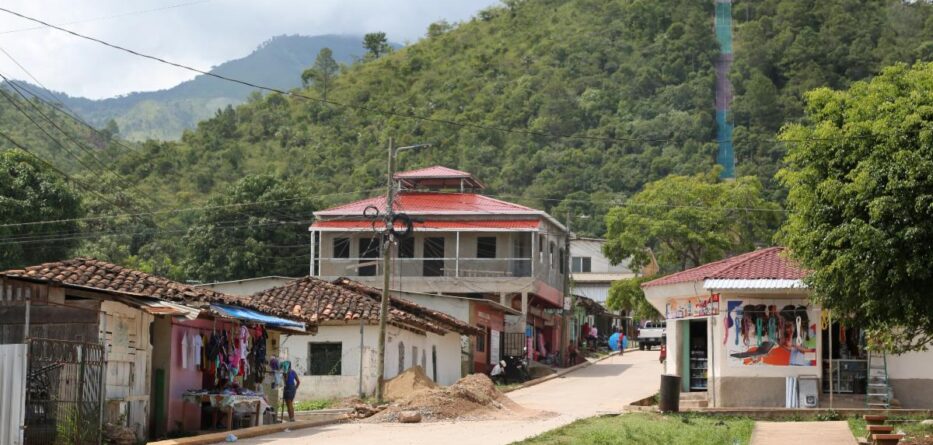

Cesar Nahun Aquino, 44, is an auto mechanic from the town of Yoritos, about 200 km north of Tegucigalpa. The town made headlines two years ago when residents successfully banded together to eject a mining company that had attempted to set up operations in the region.

A member of the Tolupán indigenous community, he ran a transportation company in San Pedro Sula before the Covid 19 pandemic, which he says eviscerated his business. Now he is back in his hometown, a largely agricultural region known for coffee, avocados, and cattle ranching.

“We’re asking for the basics, to get rid of corrupt elections, transparency, to reactivate the local economy so that it benefits people in the community,” says Aquino, a supporter of local mayoral candidate Freddy Murio, a formerly undocumented migrant who spent 12 years working construction in New York before returning to his hometown two years ago. “We have to start with our municipality before we can begin to change the country.”

Back in the capital, officials acknowledge no single election will solve the challenges confronting Honduras. But they stress protecting the integrity of the vote and securing the democratic process in November are key to repairing the ongoing damage caused by the coup in 2009.

“The only opportunity for the country to build a democratic foundation is through the coming elections,” says Rixi Moncada, a lawyer and part of a three-person rotating chair with the newly created National Electoral Council, or CNE as it’s known by its Spanish acronym.

The CNE, responsible for delivering the final vote tally once the polls close, was created following widespread irregularities and violence that marked elections in 2017. Along with the National Registry of Persons and the Clean Politics Unit — tasked with monitoring campaign finance in a nation where drug money and politics are inextricably intertwined — these three institutions are responsible for ensuring election integrity.

Moncada, a former member of the Zelaya administration, admits it is no easy task.

“No one is prepared for the criminality,” she says, referring to the ongoing political violence that she sees as an extension of the 2009 coup, including the recent murder of mayoral candidate and member of the opposition Libre Party, Nery Reyes, who was killed earlier this month. No one has been arrested yet in his murder. “We are prepared for the process.”