Mary Jo McConahay

Ethnic Media Services

GUATEMALA CITY — Residents of this largest city in Central America are waking up this week with hope in their new president, Bernardo Arèvalo, who took office in the pre-dawn hours Jan. 15 after a day of tension when his political enemies made last ditch efforts to delay the inauguration.

In a region where autocracy is rising, Arevalo’s ascension in Guatemala is being seen as a blow for democracy.

“He came in like a fish under water, nobody expected him,” said Marta Cuevas, 74, a tortilla-maker and mother of four whose face wore a look of glee as she watched Arèvalo take command of the armed forces in an open-air plaza later that morning.

Arèvalo, a 65-year old academic and diplomat, won a surprise landslide victory in August, but weathered assassination plots, exiles and arrests of allies, and legal maneuvers by judicial authorities until finally being sworn in, before an audience of heads of state and other official guests forced to cool their heels for nine long hours when no-one knew whether Congress members in a boisterous session across town would agree to validate the election.

“Democracy has overcome its hardest test,” read a local newspaper headline.

A turning of the page

Change was quickly evident. The ceremony Cuevas and others witnessed would once have been unthinkable. In a purposefully public display, hundreds of military forces in unformed ranks, including mounted cadets, naval officers, and camouflage-clad army special forces called Kaibiles, a unit responsible for some of the most egregious massacres in Guatemala’s civil war (ended 1996), pledged obedience to the civilian, democratically elected president, who took command with a discourse emphasizing human rights and adherence to the constitution.

New Minister of Defense Major General Henry Saenz Ramos committed the military’s “subordination and respect” to elected officials and spoke to the “dignity of the person.” A flyover of fixed wing aircraft and helicopters tipped its wings over the plaza, which once housed the presidential palace. The last time many in the crowd had seen that was during coups.

Arevalo’s father, Juan Jose Arevalo (d. 1990), was the country’s first democratically elected president, inaugurating what is sometimes called the “Ten Years of Spring,” an era of progressive reforms that ended in 1954 with a CIA-sponsored coup that ushered in decades of government led by, or beholden to, the military. The younger Arèvalo, with academic degrees in philosophy and sociology, worked for years in Geneva on projects that provided counsel to states in transition to democracy, and is considered well prepared for working with the military.

‘An end to corruption’

In numerous interviews about what they wanted from the new administration, Maya indigenous Guatemalans, who make up nearly half the population, spoke of an “end to corruption and delinquency,” better access to schools, respect for the territories where they lived and their natural resources, including woods and water.

Amparo Conseulo, 72, of San Andres Ixtahuatan, in the country’s far west, led her expectations with a reduction in the cost of the “canasta basica,” or basic “basket” of food items such as beans and rice. “We want electricity, water, decent houses, work.”

Consuelo and other women from their town travelled 11 hours to witness Arèvalo’s address to supporters in the central Plaza of the Constitution where, because of delays by Congress, they waited until 3 a.m. to see the new president who came in person to thank them.

Consuelo had little doubt about where opposition to Arevalo would continue to come from—the country’s business elite and Justice Ministry officials who attempted to block him from taking office.

“First he has to thank God, then deal with CACIF,” she said, the lobby that represents the country’s most powerful businesses, the Coordinating Committee of Agricultural, Commercial, Industrial, and Financial Associations. He had to “eliminate” functionaries on the take, she said, “beginning with the judicial organisms.”

By law Arevalo cannot fire Attorney General Consuelo Porras, who oversaw opposition to the election results in the courts, but on day one of his presidency he asked for her resignation.

Indigenous leadership

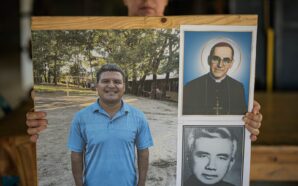

The months-long, grueling show of resistance to official attempts to reverse election results was led by indigenous authorities, who caused roads to be blocked, kept up a constant flow of informational meetings and communiqués and organized an extraordinary 106-day peaceful siege of the Justice Ministry to pressure for respect for the vote.

Maya from far-flung communities took turns sleeping on the sidewalks, displaying banners, providing food, and holding religious ceremonies by their spiritual guides. They attended outdoor mass given by the highest Catholic prelate in this Catholic country, Cardinal Alvaro Ramazzini, who is close to Pope Francis. Through it all the indigenous resisters carried not the flag of Arevalo’s Semilla political party, but the blue and white national banner.

“It’s not Arevalo they are for, it’s democracy,” said Santiago Bastos, a long-time scholar of Guatemalan ethnicities now at the Center for Research and Higher Studies in Social Anthropology in Guadalajara. Bastos was observing inauguration week events.

Nevertheless, in the uncertain months between the election and inauguration Arevalo continually recognized the key role of the indigenous in protecting the vote that made him president. He often used the term “The Four Peoples” when speaking of Guatemalans, referring to distinct groups that make up the Guatemalan population – Maya, Garifuna, Xinca, and the ladinos or mostly white people who have run the country since the 16th century Spanish conquest.

Arevalo’s first stop after inauguration in the National Theater, was to visit the Maya keeping vigil outside the ministry, in the middle of the night, and the next day he attended a Maya religious ceremony at Kaminal Juyu, an ancient site at the edge of the capital.

He has named dozens of Maya administrative ministerial personnel and a member of his cabinet, Labor Minister Miriam Roquel, is Maya.

Still, Arévalo is already receiving some criticism for not naming more Maya now to highly visible positions, although he has pledged to do so, as he said in his appearance in the public plaza after the inauguration, “to make them participants in making the decisions, recognizing them and taking in their wisdom…No more discrimination, no more racism.”

High expectations

Arevalo’s concerns and constituencies are many, and he will have to move and fund them without support of a majority in Congress. He immediately recognized responsibility to Guatemalan migrants – 55,000 were deported from the United States in 2023, a 36 percent increase over the year before, but said migration must be recognized as a “global” issue demanding international solutions.

Guatemala would do its part, he said, caring compassionately for the thousands of Salvadorans, Nicaraguans, Hondurans and Venezuelans, for instance, who appear on their way to the United States – some can be seen begging on the streets.

A leader of one of the many cultural groups who came to the capital to celebrate with the crowds, Francisco Marcial, 58, a Garifuna professional musician, said that with Arévalo, “We hope in God to open the doors to decentralize government operations” to bring attention to towns like his, Livingston, on the Caribbean coast, whose residents are of African descent, and to include their history, as the Maya are included, in the national school curriculum.

Arévalo, who emphasizes women’s rights, will preside over the country’s first gender-balanced presidential cabinet, and in the military ceremony in the plaza pledged to name the army’s first female brigadier general.

But for some advocates that is not enough.

Angela Mariela Romero, 46, legal representative of Trans Queens of the Night, a transgender support group that has observer status at the Organization of American States, has survived four assassination attempts and wants the new president to do something to confront attacks against LGBTQ+ persons. She said that “we want a law on gender identity” passed in Congress.

“The expectation of the citizenry is high,” said an editorial in the country’s largest daily, Prensa Libre. For Arévalo’s new government, it said, “that constitutes the greatest challenge.”