Art is an important aspect of the holiday of remembrance, which is celebrated between October 31st and November 2nd

Arturo Hilario

El Observador

The art of Día de los Muertos, much like the holiday itself, is as much about life as it is about the remembrance of those no longer on this mortal plane. It is as much a celebration of life, the joy of it, and bringing to mind those that lived and are now gone.

A mixture of cultures itself, it interweaves indigenous Mesoamerican Aztec beliefs with the Spanish Conquistador’s holidays of All Saints and All Souls Day.

In the US, the holiday has seen a steady rise in popularity. Yet unlike Saint Patrick’s Day, or even Cinco de Mayo, the cultural and traditional purpose for Día de los Muertos’ existence is heavily protected by those that celebrate it, not letting it lose its meaning.

Artists are a crucial part of the movement, and creating and building upon the iconography of Día de los Muertos. By capturing their unique perspectives, they open up a greater audience to participate and learn of the holiday.

One of the first and unlikely keys to creating the art of Día de los Muertos was a political cartoonist and printmaker from the late 19th century whose work became iconic with Mexican folk art. José Guadalupe Posada used skeletons, or ‘calaveras’ as tools to show political strafe between the upper and lower classes. One of his most famous creations, arguably the most iconic imagery of a calavera is called “La Catrina” and is a skeleton woman with a large hat.

It was not until after Posada’s death in the early 1900’s that his work began to be appreciated as folk art and incorporated within the day of the dead celebrations. It was this type of imagery, of skeletons doing things in our world, whether it was dancing or even protesting, that stuck with the art style of the holiday.

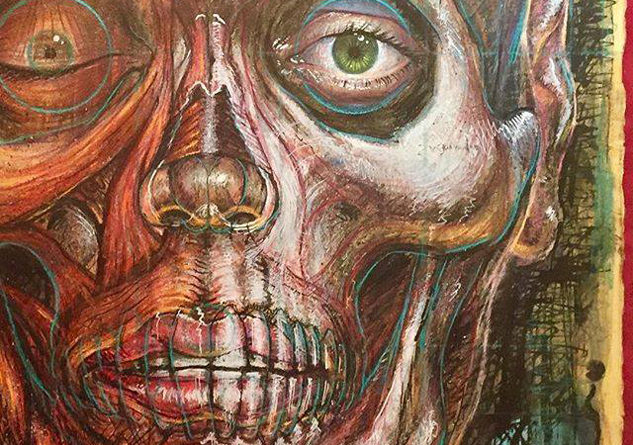

Fine artist and muralist Francisco Franco, who has an art studio called Francisco Franco Studios in San Francisco, is one of the artists whose style blends the world of day of the dead with his own life experiences.

Franco has a fascinating backstory which helped mold his artistic signature and ultimately helped him become closer to the November holiday and its traditions.

He states that although his direction into art wasn’t pushed by the environment in which he grew up in, the pieces of his Mexican-American identity were always there.

It wasn’t really pushed [into art]. My mother passed away when I was ten years old, she put me into classes. My dad didn’t know anything about [art], he was just a mexicano working. So, I just kind of stopped doing and it wasn’t until my senior year in high school that I began to think, what am I going to do with myself? And one of the ideas was doing art. I took a class at community college, and I ended up running from there.”

After getting a full sponsorship at UC Berkeley Franco then transitioned to the New York Academy of Art, where he broadened his studies

“I witnessed 9/11 when I was there, about 8 blocks from me. Then we were sent to Oxford to study cadavers, so we were drawing stuff like that. So, the whole idea of death kind of stuck in my mind.”

Franco says this point in his life really had a toll on him in a dark way. Not only did he see firsthand the effects of the September 11th, 2001 terrorist attacks, but in this time frame also lost his mother and had health issues which resulted in a somber approach to his work, and to life in general.

“The idea of death really sunk in my head. Having friends die, having my mother pass away. Growing up in gang culture I had a lot of friends pass away but the whole idea of death, and drawing cadavers, just really sunk in and I started having an existential crisis. And it terrified me, and I wondered why we weren’t talking about it, doing anything about it.”

This push towards examining death and dealing with the darkness that affected Franco led him to work on a mural which in turn transformed him, for the better.

“I was commissioned to do a big mural, at a taco restaurant. I was tired of people asking me if I was a Chicano artist or not, so I thought, ‘you know, I’m gonna do a very Mexican piece that’s gonna represent different parts of who I am.”

As for his own history with the holiday, Franco’s Mexican-American upbringing didn’t include much to do with Día de los Muertos.

“I wasn’t raised with it, but I knew of it. My dad is from Chihuahua, he’s an immigrant. My mother was like third generation and my grandfather was born in native California, so I have this immigrant side to me, this more Americanized side, but it was still Chicano point of view.”

It was because of this fragmented memory of the holiday that Franco says he hit the books, doing research at the Chicano Studies Library in San Jose. There he encountered a lot of references to the day of the dead. It was during this time period, in 2000-2002, that Franco says there wasn’t too much happening in regard to day of the dead celebrations in the local community.

“It wasn’t as popular as it is now so when I brought the idea up to my friend that owned the restaurant, I said, ‘just trust me on this one, it’s gonna be fun, and there’s going to be a message behind it.’ So I painted the large mural, it was an homage to José Guadalupe Posada, his work really inspired me.”

The popularity of this mural and what was behind its meaning gave Franco the positive reinforcement he needed at that point in time. It also helped cement what his style would evolve into.

“As I was doing this thing I came to a lot of conclusions. So in that painting they’re (calaveras) dancing, they’re having fun, they’re eating, listening to music. All the things we enjoy in life, and so I just realized, while I was doing that painting, you can’t be thinking about death, we’re already going to die anyways so let’s go ahead and ‘disfrutar’, enjoy life. Because in a way we’re already dead, we all have to face it. So that just sparked something. It became a real powerful thing.”

As Franco began to get requests for commissions for day of the dead styled portraits and murals, he began to develop his body of work, and the identity he says he uses in his art.

“It was very healing, and I realized that especially with the Mexican-Americans that you know, we’re not quite Mexican of course, American either, but we assimilate and create this new culture within the culture. And it just stuck, and it became healing to other people.”

The process of finding his voice in art, something that he was able to do for himself, as well as translating to being visually appealing began with that restaurant mural, and his own discoveries on Día de los Muertos.

But Franco says it wasn’t until he created three specific paintings of three famous women that his style was solidified. These paintings are among his most near and dear.

“The ‘Marilyn Muerta’ put me on the map. No one was doing anything similar at the time. So it’s always going to have a place in my heart. There’s one I did called ‘La Catrina’ which is a skeleton Frida and she’s just kind of staring at you, laughing kinda. She’s got that grimace, because she’s a skull. That one, just as far as beauty and the message it’s almost cheesy, it’s beautiful yet horrific at the same time.”

The final one also holds a special place within him because of the connection to his father.

“The Selena one, ‘Amor Prohibido’, that one has a special place in my heart because me and my father [shared] something together through music, and he introduced me to her. He had met her actually. He brought a signed picture and said, ‘hey listen to this album’. And my dad was into Mexican Rancheras and I wasn’t, so we came together on that. And she tragically died shortly after that.”

Franco’s experience with finding and reclaiming that culture that is very much a part of Latinos from every walk of life goes to show how there doesn’t need to be a certain time and place to introduce Día de los Muertos, of healing through celebration and prayer.

“And that is true in every sense of the celebration. Every November 1st and 2nd there is a beautiful celebration of life, loved ones, and most importantly of cultural traditions, that ancestral connection we all share in our own ways.”

Each of us may find our own way to interpret death and losing the ones we love, and hopefully, it’s something we can find solace in, and find memories that reach out to those we don’t share a physical space with anymore.

“That’s what painting is to me. Instead of being negative and thinking of death in a way, you take all that hardship and pain and you turn it into health, make it into something beautiful. I adopted it, and it helped me go back and heal myself. And it’s my culture, even though I wasn’t raised with it, it became that. Now I have an all-year alter at the house.”